This morning, I stood in front of the bathroom sink and I couldn't remember which toothbrush was mine. None of the colors looked familiar. Hadn't I been using a green one? So why were there only blue, purple and pink brushes in the cup? I stood there with the strange sensation that I was out of time, as if I was there but not there, and then I realized that I was crying, tears were rolling down my face, and I missed her so much.

My friend Annie P died last week in Jamaica. She had throat cancer. She and I were so close in high school. I loved her so much. Even now, I marvel that it is possible to love someone as much as I loved her, and yet lose touch.

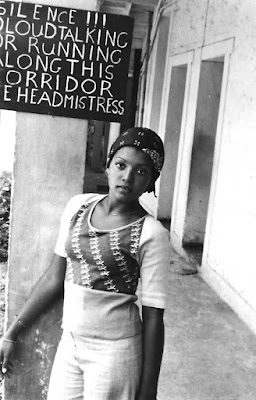

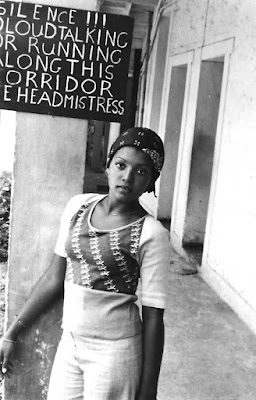

She was an artist, an astonishing pianist, and a straight-A science student. She was just gifted all around. She was a grade ahead of me, but our spirits clicked. We used to say it was because we were born on the same day, though she was a year older. We first became close in choir practices. The photograph above was taken during one of our summer choir workshops. This one was held for two weeks at a girls' boarding school in Malvern on the other side of the island from Kingston, where we lived. The school was in a very rural part of the country, and as I recall, the showers sprayed freezing cold water day and night. There was no ceiling to the concrete shower stalls. Annie and I and some of the other girls used to prefer to shower in the evenings, squealing and shrieking at how icy the water was, even as we stopped to gaze at the night sky above us, bejeweled with stars.

Annie and I laughed all the time. After school, we often took the bus up to Manor Park Plaza where we'd browse through the bookstore or the record store. We'd sit in the aisles and talk and read and giggle over the slightest thing, or we'd hole up in a record booth and listen to album after album, singing along, and the hours would pass, sublime. Suddenly we'd realize it was getting dark out, and our parents would be worried, and we'd scramble to the bus stop and head in our separate directions home.

In her final year of high school, Annie discovered that her mother hadn't given birth to her. She had overheard her aunts talking. Annie was cut to the quick. I remember we were walking along Constant Spring Road when she told me. "So guess what?" she said, her tone deceptively flippant. "My mom is not my mother and my real mother didn't want me." And then she started to cry. I tried to comfort her with all the words a 16-year-old can think to muster. And then we just walked for a long time in silence, holding hands. It turned out that her father had had an affair on a business trip to the Cayman Islands, and she was the result. He brought her back home to his wife, who took in the baby girl and raised her as her own. Annie's mom, Auntie Lulu we called her, could not have loved her more if she had issued from her own womb. And Annie did know that. But I think she never recovered from the news that everything she had known to be true about herself, was in fact not the case. I think she never again felt rooted.

Our bond slipped a little the year she had an affair with her cousin's boyfriend. We were 20 and 21 then. She was in medical school in Jamaica and I was in college in New York. I didn't know how to be excited with her about this guy, I didn't like him, and I didn't know how to caution her. I didn't know how to tell her that I thought what she was doing was wrong, that her cousin would be devastated. I want to think that I tried to tell her this, but she couldn't take it in and I didn't have the heart to push harder, to make her feel judged. Later, when the affair came to light, she and her cousin, who until then had been like her sister, became estranged. Their estrangement lasted for the rest of Annie's life.

The threads unraveled a little more in the years that followed. Annie started drinking heavily after her ill-fated affair, and she never really forgave herself for wading into those waters. Sometimes, I wonder if she was trying to understand her father and the infidelity into which she was born. She did manage to finish medical school and become a doctor, even though I have often suspected that a career in the arts would have suited her temperament much better. She married and had a son the same year that I had my daughter.

But we were never again as close as we had been in high school. It had become difficult to hold a coherent conversation with her. I still loved her. But now I always had the sense of being adrift in her presence, as if I couldn't reach her through the haze of intoxication, or maybe some of her brain cells got pickled. It didn't help that we only saw each other when I visited Jamaica once or twice a year. Over time, I settled for news of how she was doing from mutual friends, and the occasional long-distance phone call.

And then came the news that she had a tumor on her vocal chords. She had gone to a doctor to check out a dry hacking cough that wouldn't go away and the loss of her voice. The doctor in Jamaica essentially told her it was untreatable, to save her money and have a nice funeral. So she flew to New York for treatment. She arrived last July and stayed until December with a cousin in New Jersey, traveling into the city daily for chemo and radiation. Just before Thanksgiving, she told us that the tumor was gone, she had been given a clean bill of health and would be going home in two weeks. She had Thanksgiving dinner with us in our home. Her voice was back, she was laughing and talkative. She looked great.

She flew home the following week. That was in early December. No one knew she was back in the hospital until last week when someone texted Annie's cousin, the one from whom she had been estranged, and said they'd seen her there. We don't know if Annie had instructed her husband not to call anyone. The tumor, if it ever really left, was back with a vengeance. It had reached down into her lungs and circled her spinal chord. She couldn't eat, she couldn't breathe. And last week Friday at 3:30 in the afternoon, with her husband and son on another floor talking to her doctor, she left us for good.

I miss you Annie P, and selfishly, I miss us. The times I spent with you in that bookstore or at choir workshop or listening to music in the record booth or just walking aimlessly and talking, may well have been the most carefree moments of my life. So I thank you for those. My dear friend and sister in spirit, I thank you for having loved me then as I loved you. And I pray you are at peace.